How crypto investment scammers peddle celebrity deepfakes online with ease

Deepfakes of famous faces are still flooding digital platforms to promote phoney crypto schemes and other cons, Which? data shows, as banks report £98m stolen by investment fraudsters in the first half of the year.

Celebrity deepfakes were the most common scam advert reported to the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) in 2024, and these scammers appear to be relentless. New figures from UK Finance show that investment scam losses reached £98m in the first six months of 2025, a 55% increase year-on-year.

Which? data points to a similar trend – we’ve received over 200 reports of investment scams to our Scam Sharer tool so far this year, almost half of which originated online or through social media.

Here we unpick what our data shows, including the most commonly-imitated famous faces. We also hear from a devastated former police officer who lost thousands after seeing a mock BBC article about crypto trading on Facebook.

Sign up for scam alerts

Our emails will alert you to scams doing the rounds, and provide practical advice to keep you one step ahead of fraudsters.

Sign up for scam alerts

Social media is a gateway for investment scams

Fraudsters spread their lies furthest and widest by paying for adverts on Meta (which owns Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp) and Google (which owns YouTube), yet there are currently no provisions for these tech giants to compensate the victims of scams on their platforms.

Of the 203 people who reported investment scams to us between January and mid-October, nearly half (48%) said they came across the scam online or through social media. Only telephone investment scams came close (34%), and we suspect at least some of these people had left their contact details on dodgy websites first. Other methods were far less likely to be reported, such as email (8%), messaging apps (4%), letter (3%) and text message (2%).

Buying adverts and posting on social media is an effective way for criminals to lure in victims – over half (56%) of those targeted this way said they lost money, compared with only one in six (20%) victims targeted by telephone.

Most people didn’t mention a specific platform to us, but Facebook stood out, named in 38 reports, while the likes of Instagram, TikTok, WhatsApp, X (formerly Twitter) and YouTube were only mentioned in a handful.

- Find out more: more than half of bank transfer scams originate on Meta

‘I lost £162k on a fake investment website’

The ramifications of falling for a scam can be shocking, with victims who were scammed online or via social media reporting average losses of £11,865, though one individual lost more than £162,000.

He was drawn in by what he thought was a genuine BBC article on Yahoo, promoting a company using the name ‘RoxoFX’ – now listed on the register of potential scams by the financial regulator.

‘I called them and was encouraged to save a little. They were very personable and professional. I was shown how their investment website worked and was able to choose which scheme I preferred. I was then encouraged to invest much more and take out loans, after a financial plan was made for the future.’

‘They played on my emotions, needing security for my family, to support my disabled daughter at university. After I invested all this money, they stopped communicating with me.’

Watch out for bogus BBC news stories

Fraudsters routinely create fake news articles to plug their sham investments. Earlier this month, we found eight deepfake crypto scam videos on YouTube. All eight were removed after we reported them, and YouTube told us that it doesn’t allow phishing content on its platform.

But readily available artificial intelligence (AI) tools can help scammers to create images, audio files and videos to imitate people with frightening ease. Our insight points to Martin Lewis, Prime Minister Keir Starmer, Piers Morgan, Elon Musk, Nigel Farage and Richard Branson being among their favourite faces to deepfake.

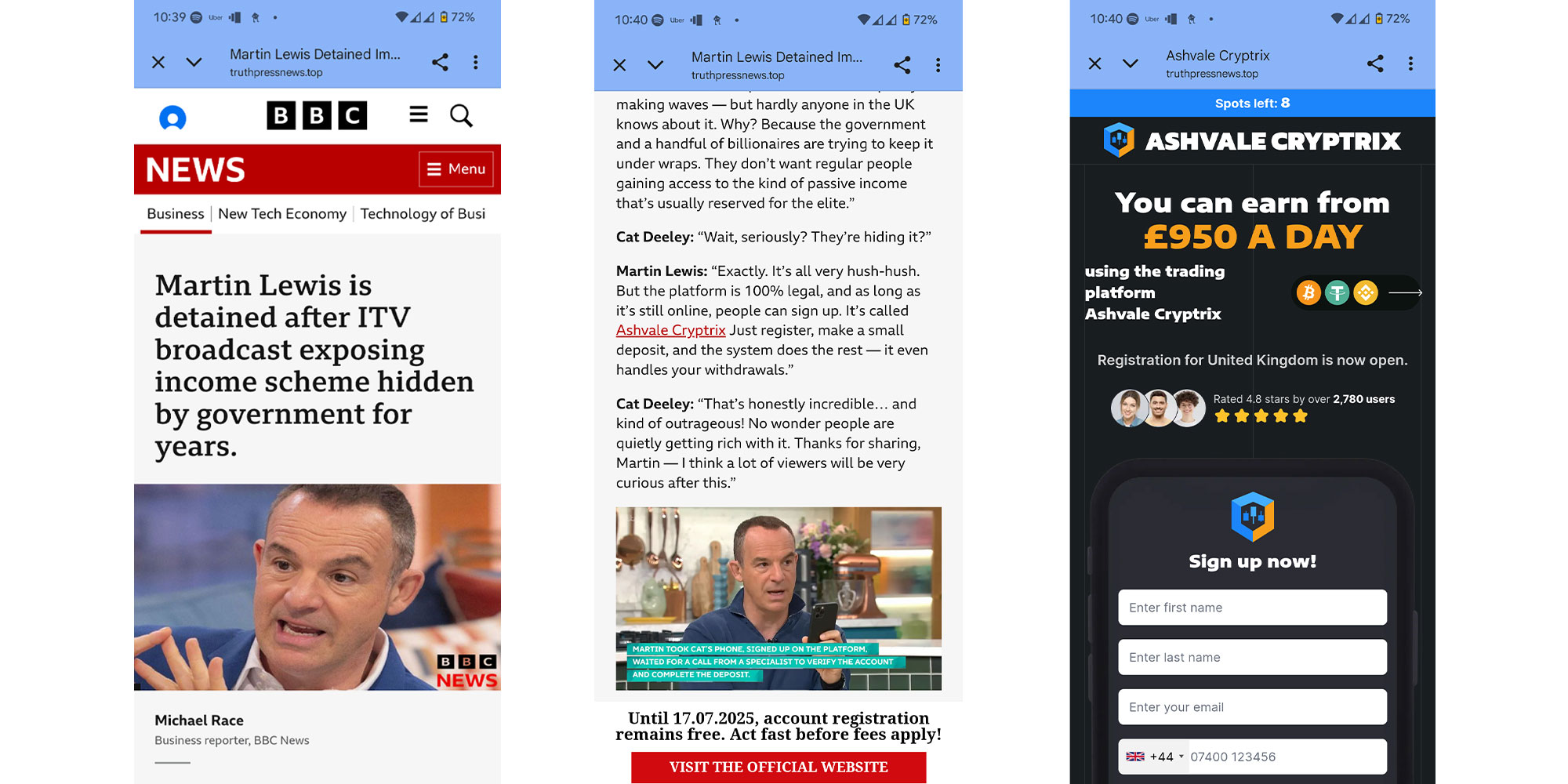

In July, we found adverts linking to a fictitious BBC story within minutes of checking Facebook, apparently showing a transcript and video of a This Morning interview with Martin Lewis, who wanted to tell the British public to invest in ‘Ashvale Cryptics’.

These posts were only live for two days before they were taken down, but this is long enough for criminals to do their dirty work. They can also simply start again – a suspiciously similar Facebook scam reported to us earlier in the year appeared to show BBC presenter Amol Rajan interviewing Piers Morgan about a new AI investment tool that tracks the stock market, for example, with investors only needing £200 to start and ‘watch the money come in’.

Meta sells ad space to crypto scammers

We shared the scam adverts we found with Meta, asking if it accepts that it repeatedly fails to stop fraudsters abusing its advertising programme. We also pointed out that this particular advertiser had last posted in 2021, making it likely the account has been taken over by scammers. Meta didn’t answer our questions but provided some general background on its approach to fraudulent ads, which we summarise below. We think it would better protect the public if it made additional checks on advertisers linked to accounts with long periods of inactivity.

Tackling this problem requires tougher action. Media research firm Fenimore Harper reported last year that 43% of all Meta adverts about Prime Minister Keir Starmer were fakes, after rogue advertisers spent £21,000 on over 250 adverts in just one month, reaching up to 891,834 people. Earlier this month, it also found dozens of active adverts promoting ‘Quantum AI’, a global scam Which? first reported in 2024, including some linking to fake BBC articles featuring deepfakes of Martin Lewis and Peter Jones from Dragons’ Den.

Meta removed the offending ads and explained it doesn’t allow fraudulent activity. It works with law enforcement to support investigations and keep scammers off its platforms, and uses technology to identify and flag AI-generated or edited content, including celeb-bait ads. Users can report ads they believe violate its policies by clicking the three dots in the upper right hand corner of the ad.

Martin Lewis deepfake created by scammers

Fake Keir Starmer interview lays crypto scam trap

Karen (not her real name), 61, a former police officer from Belfast, lost £2,350 after being targeted with celebrity deepfake ads. She noticed a Facebook advert showing Keir Starmer and Piers Morgan discussing investment bonds back in February. Later that day, she saw another video, this time featuring Martin Lewis, which appeared to promote the same bonds.

Assuming these were legitimate news stories, she entered her contact details. Within days, she was called by two ‘bond traders’ offering her the chance to purchase crypto investments which they would manage. They were knowledgeable and polite, telling her the money would be invested for approximately one week, and she could withdraw any profits before deciding if she wanted to invest again.

Money was extremely tight at the time – Karen has been unable to work due to ill health – and she agreed to invest the equivalent of $250 in both, using her Halifax credit card. ‘It was all very cleverly done, but, for me to withdraw even my own money, I had to invest a little more. They led me through setting up an account through Crypto.com and then Crypto-onchain and asked me to open an app on my iPad called AnyDesk,’ she explained.

The scammers knew when to turn the screw, telling Karen she needed to transfer a further £2,000 into her trading accounts before they could release any funds. They were aware this was every penny she had after accessing her computer using AnyDesk, a remote access tool.

‘I was in a state and the scammer heard me sob. He said l was just emotional at that moment and that he would help me. I sent the money from my Halifax account.’

Fraudsters abusing the UK payments system

Halifax did try to warn Karen about scams when she made the bank transfers, but it failed to break the spell. The fraud was only uncovered when the scammer's excessive greed – urging her to take out a loan – finally prompted her to contact the bank and police.

She got £350 back for the initial credit card payments, but the bank refused to reimburse the £2,000 lost via bank transfers to Crypto.com via its processing provider, ClearBank. As directed by Halifax, Karen contacted ClearBank, which in turn directed her to Crypto.com.

Getting nowhere, she came to Which? for help. We contacted all three firms about her case. ClearBank said Crypto.com ‘holds the consumer relationship and is responsible for conducting the verification process when the account is opened and ongoing monitoring of activity.’ Crypto.com told us it immediately disabled the account once it had been reported and ‘maintains the highest levels of security protocols and procedures to prevent, detect and tackle any such issues.’

Halifax explained to us that the transfers to ClearBank were in her own name, to an account that she had access to, meaning they were not covered by mandatory reimbursement rules. However, upon learning that neither ClearBank nor Crypto.com would take responsibility, it agreed to cover her losses.

- Find out more: one year of the reimbursement scheme for bank transfer scams

UK fraud regulations need to toughen up

The scam adverts we found are likely to fall within the scope of the Online Safety Act (OSA), yet only parts of this regime are in force.

Ofcom has delayed publication of draft rules tackling scam ads and protections are unlikely to be in place until 2027 at the earliest. This means that while scams appearing as ordinary YouTube, social media and search engine posts are currently covered, scams being spread by paid-for adverts are not.

Given the delays up to this point, Which? is calling on the government to impose a statutory deadline for Ofcom to introduce the codes of practice and make sure its forthcoming fraud strategy includes a commitment to legislation on scam ads not covered by the OSA and measures to hold Big Tech to account for the volume of fraud perpetrated by third parties on their platforms.

- Find out more: follow our Stamp Out Scams campaign