Healthy living

Use our expert advice and recommendations to live your best life every day.

Get started

The UK 'traffic light' food labelling system is intended to help people identify how healthy or unhealthy food and drink products are.

However, Which? research has found that the government-recommended (though not mandatory) scheme is applied inconsistently, confusing shoppers.

Some retailers and brands don’t use any colour-coding, meaning you can't tell at a glance if something is high in fat and sugar or not, while others don’t display the traffic light system on products at all.

Shoppers told us they do use the labels and find them helpful, but they aren't always sure what they mean.

Based on our research, we think there's a need for an updated and simplified approach that is consistently applied to help shoppers make healthier choices.

We found differing approaches to marketing the same product.

In the case of pizzas, for example, Crosta Mollica, Pizza Express and Italpizza la Numero Uno had no front-of-pack nutrition labelling, while other brands, such as Dr Oetker and Chicago Town, had black and white labelling without the traffic light colours.

This makes it harder for shoppers to compare products and quickly identify those high in fat, sugar, or salt.

And shoppers do use these labels. Our consumer research, conducted in April-June 2025, found that a third of participants said that the nutrition label was the first thing they looked at on the front of the pack when choosing a product, after the brand and price.

People most often used traffic lights when deciding between snacks (56%), dairy products (33%) and breakfast cereals (27%). Nearly half found the traffic light label easy to understand without much thought, and one in four said it helps them make quick decisions while shopping.

Sue Davies, Which? Head of Food Policy, says:

'The UK is in the midst of an obesity crisis and it’s clear that a better approach to front-of-pack labelling is needed to help shoppers make healthier choices.

'Which? is calling on the government to ensure that all manufacturers and retailers use front-of-pack nutrition labelling – ideally by making this mandatory. Our research shows that people still prefer traffic light nutrition labelling, but that the current scheme needs updating so that it is clearer and simpler and works better for consumers.

'The new system should be backed up with effective enforcement and oversight by the Food Standards Agency and Food Standards Scotland – so shoppers have full trust in the labels on their food.'

We've compared options from Boots, Centrum, Holland & Barrett and more to find the best multivitamin supplements

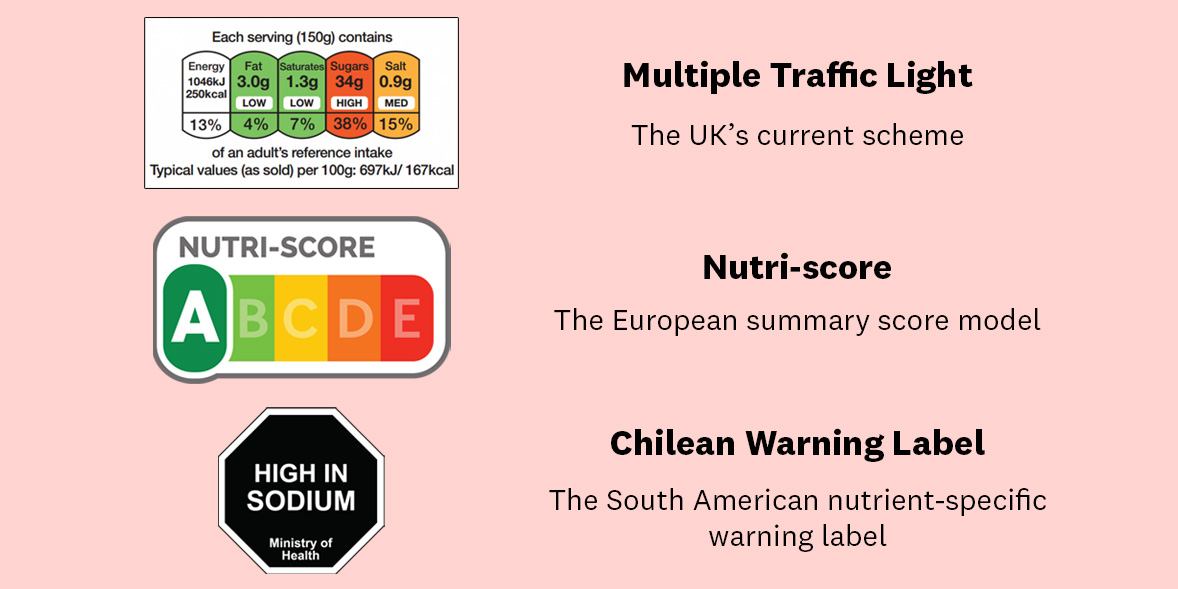

Alternative labelling schemes have emerged in other countries since the UK adopted its national scheme more than a decade ago, most notably the ‘A-to-E’ colour-coded Nutri-score used in several European countries, which rates the overall healthiness of a product rather than breaking down individual nutrients, as the UK system does.

Chile, meanwhile, uses front-of-pack warning labels to flag products high in unhealthy nutrients. But our research suggests shoppers prefer the traffic light label overall.

One participant said: 'I appreciate the traffic light system for its convenience in helping me quickly determine if a product is a good or bad choice, its simplicity which makes it easy to teach my children to use in the future, and its role in ensuring I make healthy choices for my kids despite my limited time.'

When we asked focus groups to evaluate three different nutrition labelling systems — including the European Nutri-score and the Chilean warning labels — the UK's traffic light system was almost everyone's preferred label.

Participants felt that these labels should be a requirement on all food products and that (with a few simplifications) it would support more confident, healthier choices.

That being said, the traffic light scheme is not perfect. A common concern across all participant groups was that the suggested serving sizes often do not match how much people actually eat.

Many noted they might consume two or three times the portion listed, meaning the calorie and nutrient information can be misleading. This is something we found in our 2023 investigation into the problem with portion sizes, along with similar concerns among children's snacks.

Participants also suggested removing percentage reference intakes, which can be difficult to understand, and using consistent portion sizes.

Plus, there was a demand for larger labels. We found that a quarter (25%) of supermarket task participants wanted the label to be physically bigger so it stood out more on shelves, making it easier to see, read and compare at a glance.

Use our expert advice and recommendations to live your best life every day.

Get startedWe undertook consumer research via several trusted third parties between April and June 2025.

We captured real-time insights from 512 participants via their mobile phones to observe daily routines and natural shopping behaviours.

This is a large sample for this kind of in-depth research, allowing us to explore consumer behaviours, decision-making and experiences in far greater depth and across a much broader range of households across the country than is typically possible with traditional qualitative research.

Moreover, in-depth research groups were conducted with 31 participants to explore how consumers understand, interpret and value different nutrition information labels when given time to reflect and compare each across different food products.

Find out why you can trust Which? and how we stay editorially independent.

Zoe app review: Is it worth it? Our expert nutritionist gives her verdict