Support investigative journalism

Our award-winning investigations help us in our mission to make life simpler, fairer and safer for everyone.

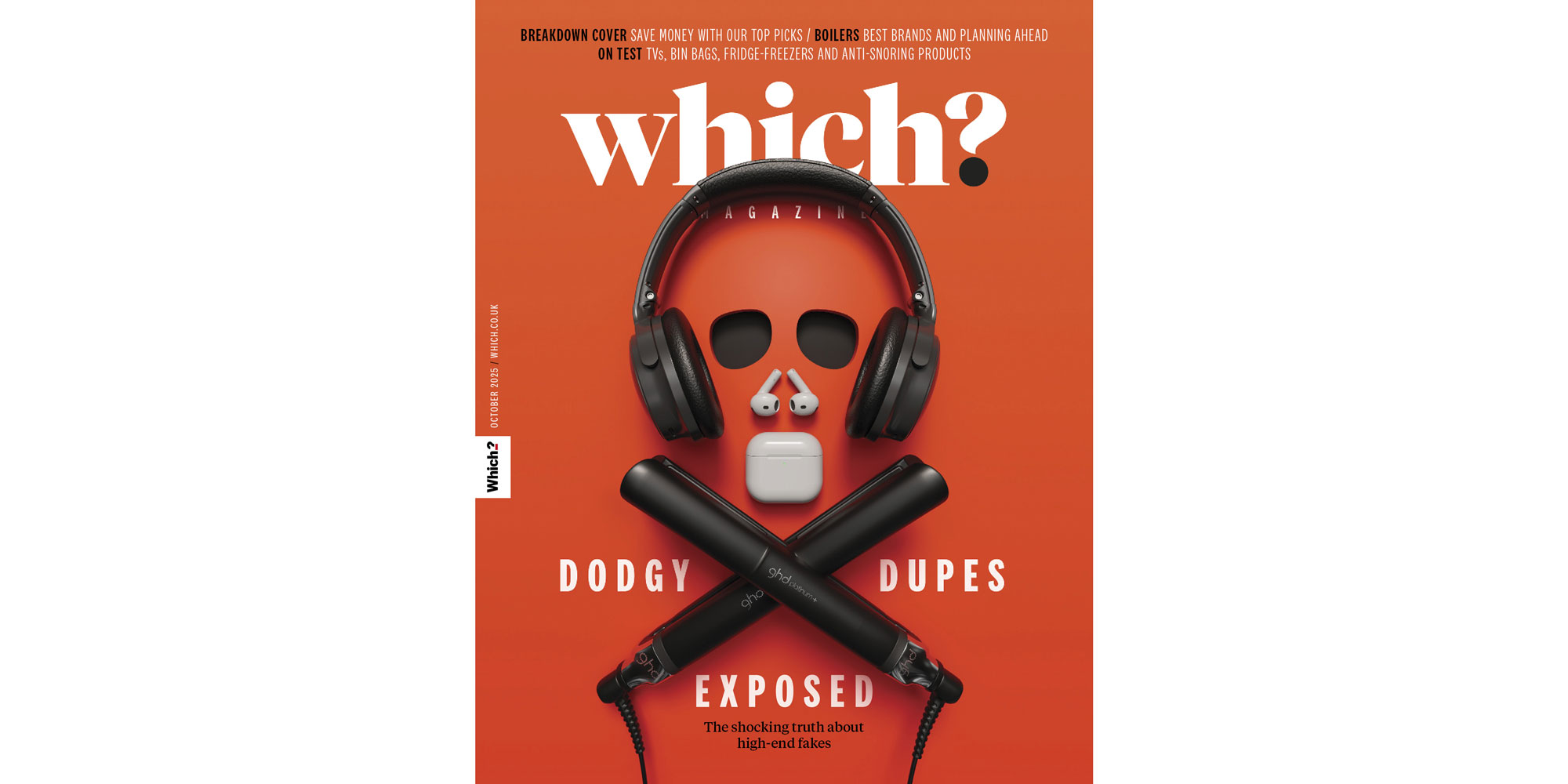

Join Which?Not long ago, counterfeit products were usually comical-looking knock-offs that no one would fall for.

But now there’s a new threat in town – the high-end fake. These new counterfeits are shiny, polished and very plausible. At first glance, many are indistinguishable from the real thing.

But behind those convincing exteriors lie very dark secrets. Our investigation found dangerous components – including dupes with fake fuses, which make them a major fire risk – and we report on links with organised crime.

Here, we expose these new types of fakes, and go beyond what you can see with the naked eye. We examined everything, from their components to their sound quality, at specialist laboratories.

We also reveal that, despite this rising tide of counterfeits, many Trading Standards teams are deprioritising work on tackling fakes. We’re calling for the overhaul of an enforcement system that is failing consumers.

We bought eight products we suspected might be fake from third-party sellers on a range of popular online marketplaces: Amazon Marketplace, eBay, Temu and Vinted.

These included a Dyson hairdryer, GHD hair straighteners, Apple AirPods, an England football shirt, Ugg boots and a Disney Stitch toy – all items are made by brands known to be targeted by counterfeiters.

It took us just a couple of seconds to find products that looked suspicious. They all had red flags: claiming to be new and unused, selling for under the market rate (although some still had hefty prices), and several had reviews questioning their authenticity.

We also bought their genuine counterparts, direct from the brands themselves, to help us compare.

So, how do you tell an item is a fake?

At first glance, almost all the products looked identical to the genuine ones. We examined what they looked like, how they felt, how much they weighed and how they handled. Often, the differences were barely noticeable. But once we spotted them, they were hard to overlook.

Here are the suspected fakes alongside the genuine items. Can you tell the difference?

We sent the electrical items to be inspected by experts at campaigning charity Electrical Safety First. They checked everything from the length of the plug pins to the temperature of the hair straighteners and the types of cable used – before prising open the casing to see what was hidden inside.

What they found was shocking.

Both the hairdryer and the hair straighteners had fake fuses – a major fire risk.

The pins on the hairdryer plug were too short to meet the British Standard. And the straighteners had a much older type of circuit board.

Giuseppe Capanna, from Electrical Safety First, said both products were a major safety risk and could prove lethal if used with wet hands. He told Which?: ‘People don’t understand the dangers of buying counterfeit electrical products – they look the same, they still seem to do the same job – but the reality is that the genuine products cost more because they use higher-quality components. They are tested. Counterfeit sellers are putting a lot of people’s lives at risk.’

We also sent the headphones to our labs for a listening test. For the Bose headphones, this found no meaningful differences. But for the Apple AirPods, while it found the genuine ones operated as strongly as expected, the fake ones were ‘very bad’.

The report said: ‘The frequency response was awful, with almost no bass at all, and a big midrange peak. We couldn’t get noise cancellation to work in any meaningful way… There is no way that the fake headphones would pass Apple’s quality control standards.’

The maximum volume was, however, fairly close, and the battery life quite close too, at 234 minutes for the real ones and 223 for the fakes.

Our award-winning investigations help us in our mission to make life simpler, fairer and safer for everyone.

Join Which?The problems are likely to extend even further. Fake toys are often made with weak seams, easily accessible button batteries and breakable parts – and that’s before you think about the dangerous dyes, banned chemicals (some linked to cancer) and flammable materials that can be used.

And it’s not only toys. Fake fashion has been found to use dangerous levels of arsenic, cadmium, phthalates and lead.

Phil Lewis, director general at Anti-Counterfeiting Group, told us: ‘Criminals don’t care about consumer safety; they will use shortcuts and cheap, dangerous materials and ingredients, including toxic dyes and carcinogens and sub-standard electrical parts that often explode. Even seemingly safe clothing can often contain toxic colour stabilisers on cheap materials that often fall apart.’

It’s not just about the products. When you hand over your hard-earned money for a fake football shirt or a knock-off pair of shoes, you may be inclined to think it’s a victimless crime.

But counterfeits are often linked to other types of crime, including child labour, fraud, prostitution, modern-day slavery, illegal drugs, trafficking and terrorism. Often, illegal drugs and weapons will be transported alongside the counterfeits on the same illicit trade routes.

For example, when police in Manchester seized 30,000 fake football shirts in 2022, they found among those working in the shops selling them were children who had gone missing from asylum-seeker hotels in England.

Often, the working conditions of the people making the fakes are horrifying. In 2020, authorities in Spain uncovered a counterfeit cigarette factory in an underground bunker, with people forced to work in dangerous conditions and not allowed to leave on their own.

And, according to a Europol report published in 2020, Northern Ireland paramilitary groups have been repeatedly found to trade in counterfeit goods, including Premier League football shirts, to fund their activities.

Mr Lewis told Which?: ‘Consumers need to be aware that organised crime gangs make use of forced labour of vulnerable families and children to produce their menacing products and there are proven links between counterfeiting, drugs, guns and people trafficking.

‘Sadly, many people are unaware that by buying a fake they’re potentially helping to fund the activities of international criminals that threaten our families, our national security, economies and jobs. Counterfeiting is not a victimless crime.’

There’s no denying fake goods are big business. And they are a growing problem as globalisation has meant increasingly long and complex international supply chains.

Most counterfeit products come from China, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), while other key players include Bangladesh, Lebanon, Syria and Turkey.

But supply routes and tactics are continually evolving. Fakes are increasingly produced closer to end markets and sent in the post in smaller parcels to evade traditional detection techniques. This has been fuelled by the rise of online marketplaces, which also means it’s easier to sell counterfeits directly to consumers.

The most recent figures from the OECD show that counterfeits represent 2.3% of global trade – making them a significant threat to global economic health, innovation and public safety.

Counterfeiters are highly responsive to market trends. They focus on the latest products and on popular online marketplaces.

There are also worrying trends of counterfeits in areas you might not expect, such as cosmetics, car parts, batteries, spare parts, fertilisers, food and pharmaceuticals. These can be especially dangerous.

The World Health Organization estimates that between 72,000 and 169,000 children may die from pneumonia every year after receiving counterfeit drugs. Meanwhile, a 2022 report from the OECD and the European Union Intellectual Property Office reports cases of counterfeit airbags that don’t deploy, fake brake pads made with grass clippings and sawdust, and counterfeit wheels that cracked after hitting potholes at just 30mph.

People who buy counterfeits fall into one of two camps – either they do so in the full knowledge that what they’re buying is likely to be fake, or they are deceived into thinking they’re buying the genuine article.

While three in 10 of us have knowingly bought a fake, there’s also a significant number (one in six) who say they’ve unintentionally bought a counterfeit product. This is most likely for toys, clothing and footwear, and sports and electricals, according to a 2023 survey from the Intellectual Property Office.

Buying counterfeits isn’t illegal, but those making them break intellectual property or trademark laws – which can be civil or criminal matters

It’s not just counterfeit products that shoppers need to watch out for on online marketplaces. Of the haul of dodgy products we bought, two stood out for other reasons. We thought the Samsung charger we bought from Amazon Marketplace looked likely to be fake. And when it arrived, it was very different to the genuine version. However, our electrical safety checks didn’t raise any issues. There was something odd about it, though – our experts thought it could have been second-hand or refurbished.

The Bose headphones we bought were just over half the price you would expect to pay for the genuine item – £169, compared with £290. But when they arrived they looked, felt and weighed the same as the genuine ones. Our listening test also showed no meaningful differences. But the low price of the Bose headphones was a red flag and it's unclear why they were being sold so cheaply.

Global brands have large enforcement teams to fight back. Apple has teams that work in more than 100 countries and monitor more than 150 online marketplaces, for example.

So, how is it that - in just a few seconds - we were able to find dangerous counterfeit products sold online?

There's a lack of clear responsibilities for marketplaces to prevent the listing and sale of unsafe products on their sites. But another issue is that we have a consumer enforcement system that’s no longer able to give this issue the attention it needs.

In the UK, Trading Standards is responsible for enforcing laws, including those related to counterfeit goods, that protect consumers. But data obtained by Which? under the Freedom of Information Act shows that intellectual property and counterfeit work was one of the most commonly deprioritised areas by Trading Standards in Great Britain over the past five years.

These services, based within local authorities, are in the impossible position of enforcing hundreds of consumer protection laws – on the high street and online – without the resources to meet this challenge.

Spotting counterfeits can be tricky, and stopping them even more so. Which? is calling for an overhaul of the Trading Standards enforcement system, with more scrutiny of its effectiveness, better intelligence sharing and more oversight. Without clear consequences – and a stronger possibility of getting caught – it’s difficult to see where the deterrent lies for dodgy sellers.

We approached the brands and online marketplaces involved in our investigation. Amazon, eBay, Temu and Vinted all said counterfeit products were strictly prohibited on their platforms, that they take this issue seriously and have proactive measures to prevent such listings.

Disney said: ‘We take reports of suspected infringements very seriously. We encourage consumers to always buy authentic products from trusted retailers.’

Dyson said: ‘Although counterfeit products can look almost identical to the genuine article, they are manufactured in inferior environments that compromise on quality and safety.’

It’s important that counterfeits do not end up back in the supply chain, so all the counterfeit or suspected counterfeit products we bought will be destroyed.

While it can be very hard to spot counterfeit products, there are steps you can take to try to avoid them:

This story first appeared in the October edition of Which?

Join Which? today to support investigative journalism.

Our award-winning investigations support our mission to make life simpler, fairer and safer for everyone.