In plain sight

Executive summary

Online marketplaces are central to the way we shop in the UK. In November 2025, a Which? survey commissioned as part of this investigation found that 90% of consumers have made purchases on platforms like eBay, Amazon Marketplace, Etsy, and AliExpress within the last two years, and that 24 million consumers are regular users. We also found that 78% of UK adults were confident these sites ensure products are safe [1]. This trust has increased over the last two years - when we asked the same question in 2023, this figure was 70%.

Despite the trust placed in them by the public, Which? investigations have repeatedly found that consumers are being put at risk by unsafe products sold on online marketplaces. The further failures in this report highlight the urgent need for strengthened regulation that ensures effective action by marketplaces to prevent and remove dangerous products from their platforms. For some – often infants and small children, as this report will demonstrate – it could be a matter of life and death.

The Office for Product Safety and Standards (OPSS) works with Trading Standards officers to maintain a public online database containing detailed reports of products that have been identified as unsafe or banned in the UK. Between August 2024 and August 2025, the OPSS published 702 alerts raising safety issues with a range of consumer products, from dangerous cosmetics to faulty electrical goods. We investigated every one of these safety warnings, searching for matching products on online marketplaces that were likely to pose the same risks to UK consumers.

We found nearly 800 products on online marketplaces, available for immediate purchase by UK consumers, that were highly similar or identical to products appearing on the OPSS’ safety register in the last year. For more than 200 of these, we were able to verify from the listing that they posed an immediate safety risk to UK consumers. The General Product Safety Regulations 2005 prohibit the sale of products in the UK that are not deemed to be safe. If sold as marketed each of these 200 products would be illegal to sell in the UK.

The remaining products were all highly similar or identical to products flagged by the OPSS as safety risks, but did not have a fault which could be verified through the listing. For example, products which pose a serious electrical risk typically have a fault hidden in their internal wiring, which cannot be seen in the product image. These hidden hazards are no less dangerous to consumers, and we believe it is highly likely that these products pose a significant risk. When we tested 15 of these products all but one posed serious safety risks, and the remaining product failed to meet UK regulations due to a labelling issue.

Online marketplaces currently operate without a clear legal requirement to ensure the products listed on their sites are safe. The UK, however, has a golden opportunity to act decisively on this issue. The Product Regulation and Metrology Act, adopted in July, enables the Secretary of State to impose product safety requirements on online marketplaces via secondary legislation. The government now urgently needs to use these powers to ensure dangerous products are prevented from reaching people in the UK.

Introduction

A long history of failure

The presence of dangerous products for sale on online marketplaces – and the fact that these products often reappear after being reported and initially taken down – has repeatedly been highlighted by Which? investigations. In the last year alone, Which? highlighted how easy it is to list illegal heaters on online marketplaces and uncovered dozens of unsafe products including baby sleeping bags posing a suffocation risk, counterfeit cosmetics, dangerous scam ‘eco-plugs’ that claim to save on energy bills, and the return of illegal and life-threatening 'killer car seats' [2].

Testing by other product safety experts contributes to this picture. A year after reporting that 85% of the toys they purchased from online marketplaces were unsafe, the British Toy Hobby Association found identical looking ones for sale online again and retested them – 100% were still unsafe. In previous investigations into recalled washing machines that could catch fire, Electrical Safety First (ESF) managed to find and even list recalled items (matching in model number) for sale on online marketplaces. ESF has also investigated electrical products sold online, including e-bike chargers. Faulty e-bike chargers cause fires, on average, every two days in London according to the London Fire Brigade – they spread ferociously, and have been responsible for four deaths and dozens of injuries [3]. Concerningly, when ESF conducted snapshot testing, 93% of general electrical products failed safety testing, and 100% of e-bike chargers didn’t meet the standard for UK plugs.

The government's own Office for Product Safety and Standards (OPSS) has reported similar findings: a staggering 81% of products it targeted for testing on online marketplaces between October 2021 and September 2022 were non-compliant with the relevant product regulations.

Our investigations of online marketplaces to date have been based on purchasing and testing products across individual categories of product. We have also posed as a seller to show just how easy it is to list an officially recalled unsafe product on these platforms – and then list it again without it being removed [4]. This latest research presents our most comprehensive addition to this body of evidence to date, looking across all OPSS safety alerts published between August 2024 and August 2025 to see if matching unsafe products are available for purchase in the UK.

The regulatory environment

Online marketplaces don’t have specific responsibilities for ensuring the safety of products listed on their sites. The extent to which they are required to ensure that the products listed on their platforms comply with product safety legislation and remove any products found to be unsafe is not specified, as it is when buying from traditional retailers.

UK product safety protections are built on cross-cutting requirements from the General Product Safety Regulations, and more specific requirements in regulations for high-risk categories such as toys, cosmetics and electrical goods. Responsibilities are specified for different types of economic operators, including producers, importers and distributors – but not specifically for online marketplaces.

This system is founded on a general safety requirement that producers only place safe products on the market. It also outlines specific obligations, including taking appropriate actions to avoid product safety risks, such as issuing withdrawals or recalls where necessary. When a manufacturer is based outside the UK, these responsibilities fall on importers. These requirements are supported by obligations on distributors to act with due care in order to help ensure compliance with safety requirements, including taking action to avoid risks from products that they supply, and cooperating with enforcement authorities.

The OPSS considers that in some circumstances, online marketplaces may be subject to the obligations of importers or distributors depending on their business model. Given the variety of models for online marketplaces, their legal requirements are not always clear.

The OPSS has recognised the need to clarify and modernise online marketplace responsibilities. This includes responsibilities to:

- Take steps to ensure that sellers operating on their platform comply with product safety obligations, and take action against sellers where necessary.

- Take steps to prevent non-compliant and unsafe products being made available on online marketplaces.

- Provide consumers with appropriate information, instructions and warnings about products prior to purchase.

- Cooperate with regulators, including having arrangements for responding to requests and quickly taking action to stop unsafe products from being made available.

The product safety system is supported by a market surveillance and enforcement system which is the responsibility of the OPSS along with local authority Trading Standards services. If a product in circulation is found to be unsafe, authorities can issue safety notices. These range from safety warnings, which alert consumers to a potential risk, and advise on safe use, to more serious product recall. A recall, which addresses a defect that could cause harm, can either be voluntary (initiated by the manufacturer) or mandatory (enforced by the OPSS).

The low level of accountability and limitations of the enforcement system have led to an environment where unsafe products are readily available for purchase, leaving people unprotected when they shop on online marketplaces. Based on survey work conducted for this investigation in November 2025, Which? estimates that at least 8.8 million consumers have experienced harm from faulty, unsafe, or fraudulent products bought from these sites [5]. Online marketplaces are not undertaking adequate proactive checks to prevent unsafe products from going on sale, nor are they dealing adequately with the removal of products that have been explicitly identified as being unsafe by public authorities.

The UK's golden opportunity

Earlier this year, following campaigning by Which? and other product safety organisations, the Product Regulation and Metrology Act 2025 (PRaM Act) was passed. The Act is a landmark step toward modernising the UK’s product safety framework and ensuring that online marketplaces are held accountable for the safety of products sold through their platforms.

The Act gives the government the powers to introduce the necessary duty on online marketplaces so that their responsibilities are clear, along with strong enforcement powers and penalties for non-compliance. Secondary legislation is now urgently needed to make this duty a reality.

Without these vital changes, the government risks missing this critical opportunity to close the dangerous gap in our laws and ensure consumers are properly protected, no matter where they shop.

This report

The rest of this report presents our findings as follows:

Chapter 1: Our investigation details the approach we took to find dangerous products for sale to UK consumers on online marketplaces

Chapter 2: The state of dangerous online products in the UK contains a high level view of our findings

Chapter 3: Clear and present danger explores products uncovered during this investigation where the risk to consumers is visually verifiable from the product listing

Chapter 4: Uncovering hidden risks takes a closer look at the products that are highly likely to be harbouring hidden danger not visible from their listing pages

Chapter 5: How could online marketplaces respond? discusses the measures currently in place by platforms to manage dangerous products online, and argues that most of the products we’ve uncovered could be prevented from reaching UK consumers through small tweaks to these processes

Throughout these chapters, we also present case studies which illustrate the extent to which the products we found for sale online are similar to those flagged by the OPSS.

This evidence is followed by recommendations which lay out what UK regulators could do to seize the opportunity presented by the PRaM bill to protect UK consumers from these risks in the future.

Finally, a detailed technical annex expanding on our methodology, and responses from marketplaces in full.

Chapter 1: Our investigation

This report aims to measure the extent to which dangerous products are available to UK consumers on online marketplaces, and to explore the risks faced by those who trustingly purchase them. To do this, we looked for products for sale that had been identified as unsafe by the Office for Product Safety and Standards (OPSS), the UK’s product safety regulator, and therefore should not be made available for UK consumers to buy unless manufacturers have taken action to address the flagged safety issue.

The OPSS maintains a public online database of product safety reports. These document safety issues found with particular products, usually by Trading Standards officers around the country [6], and contain information including the measure taken (eg recalled from market, rejected at the border), level of risk, a description of the hazard, etc. Most, though not all, reports contain a pdf document with additional information, including one or more images of the product.

Alerts, reports and recalls

The OPSS database contains three types of entry:

- Product recalls, which indicate a safety issue with a specific product which may require consumers to act to receive a replacement, repair or refund,

- Product safety reports, which indicate a safety issue with a product where corrective measures other than a recall, such as destroying the product at the border, have been taken,

- Product safety alerts, which highlight whole categories of products ‘with risks of serious injury or fatality and where immediate steps are requested by OPSS from businesses, authorities and possibly consumers’.

We have taken all three of these categories into consideration in this investigation. Since recalls and safety reports both highlight safety issues with a product, and since reports constitute the majority of entries on the OPSS database, for brevity we will refer to both types of entries as ‘reports’ below. Where the OPSS has issued product safety ‘alerts’, we have used them to highlight categories of products that pose an inherent or significant safety risk to consumers.

These reports provide a clear, public signal to sellers and marketplaces that the products they focus on have been found to be unsafe, and pose a known risk to consumers. To test whether these warnings were being heeded, we conducted a semi-automated search for products online that were likely to pose the same risks as products flagged by the OPSS.

Our focus on marketplaces

Throughout this report, we focus on products available on online marketplaces – defined here as sites which provide a platform which allows third parties to sell to consumers. This includes platforms which prioritise business to consumer sales (eg Amazon, B&Q Marketplace), and those which host sales from both businesses and consumers (eg eBay, Etsy). We have focused on online marketplaces that primarily or significantly host sales from traders, rather than individual consumers selling to other consumers, although research has highlighted how it is not always easy for consumers to understand this distinction. In any case, the approach that we have taken, demonstrating potential tools for identifying unsafe products that are subject to alerts, applies across the board.

We also chose to exclude non-marketplace online retailers from this investigation. These often specialise in one product area, and sell products directly to consumers rather than hosting third-party sellers. Where platforms, like Amazon, operated as both the marketplace and seller, we disregarded these listings, looking only for products where the seller was a third party. This choice was taken to allow us to focus our evidence on the current legislative gap, which leaves these huge platforms without a clear duty to take steps to ensure products sold through them are safe.

Methodology

Below we provide a summary of our methods for this research. Further details can be found in the technical annex to this document.

Collecting images of unsafe products

To find products which have been flagged as unsafe, we used an automated web browser to collect every report available on the publicly available Office for Product Safety and Standards Product Recalls and Alerts database. This data was then filtered as follows:

- Reports not published between 1 August 2024 and 11 August 2025 were removed.

- Reports for products not aimed at general consumers – for example, large industrial machines – were removed.

This left us with 702 distinct safety reports, which altogether contained 1,036 images of products.

For each product image, we used a reverse image search platform, Google Lens, to find matching images on the web. This technology works much like a traditional online search, but instead of looking for sites matching a string of text, reverse image search engines return webpages containing similar images to one supplied by a user. The results were then labelled by human analysts.

While Google Lens gave us the advantage of being able to search for products across the web, we could not guarantee that all sites would be represented equally; sites which had denied Google access to their listings, for example, would not appear. Accordingly, we manually searched 17 online marketplaces frequently used by UK consumers for four products chosen as representative of the types of unsafe products flagged by the OPSS. Manual searches were performed using key words in the search bar or, where available, platforms’ built-in image search.

Classifying matches

For each search, including manual searches, the top 25 results were checked by Which? analysts. We first assessed similarity, recording as matches only products which we could be confident were highly likely to be the same product as that flagged by the OPSS. Criteria used for matching included:

- Products with a matching identifier, such as a model or serial number

- Products with identical packaging

- Products sharing characteristic design elements

- Products which generally matched an alert, but with small cosmetic differences, such as colour, likely to be irrelevant to the risk flagged by the OPSS

We set a high bar for similarity, discarding any products:

Which we were not confident met the criteria detailed above

- For which the image supplied in the OPSS report was not of high enough quality to be confident of a match

- For OPSS reports which specified a batch number, since we were unable to confirm batch details from listings

- For OPSS reports which provided a specific corrective action which would make a product safe, unless we could verify that this alteration had not been made in the listing

- For OPSS reports for counterfeit products, where the original and counterfeit could not be distinguished from the listing

Where a product was judged to be highly similar or identical to one focused on in an OPSS report, we accessed the listing page to see whether it was currently available to buy in the UK. For each product that could be added to a cart with UK delivery, a timestamped screenshot and text record of the webpage was taken [7]. Products were also labelled according to whether we could visibly verify they posed a risk to consumers. Details of this coding are provided in Chapters 2 and 3 below.

Product testing

To better understand the likely risk posed by seemingly identical products, we ordered a sample of 15 products from the ones we found online, and sent them to accredited labs to be independently tested.

Chapter 2: The state of dangerous online products in the UK

Online marketplaces often claim to be proactive in preventing unsafe products from being sold [8]. As every product flagged by the OPSS has been identified as unsafe, you would expect online marketplaces to identify and remove these products as a bare minimum. To get a sense of how many of these dangerous products were nevertheless available to UK consumers, we used reverse image searching to find products matching 702 reports published by the Office for Product Safety and Standards in the last year.

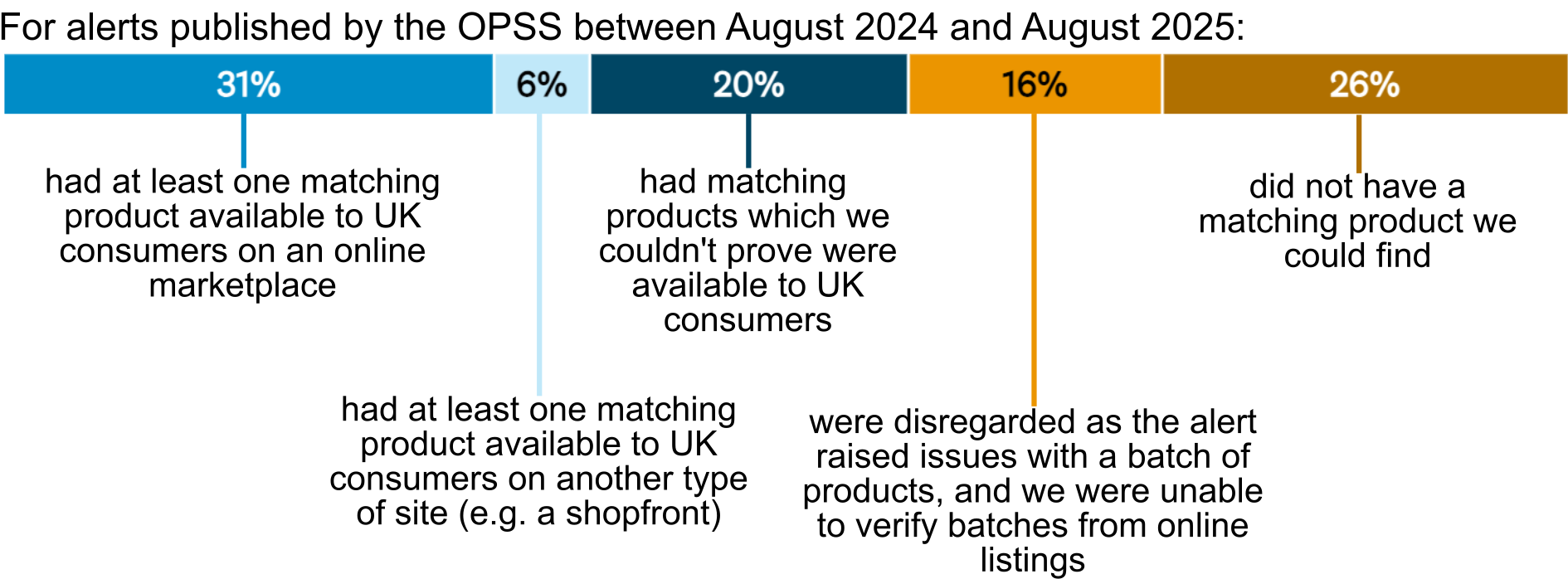

For almost a third of these reports (31%), we were able to find at least one highly similar or identical product in stock and available to UK consumers on online marketplaces. Including matches which were not the focus of our analysis – where products were available on ‘shopfront’ sites selling directly to consumers, or were not available in the UK – we found a matching product for over half (57%) of the reports published by the OPSS.

Figure 1: OPSS reports in the last year for which we found matching products

In total, we found 798 listings for products available in the UK which were highly similar or identical to a product found unsafe by the OPSS. In almost all cases, the products we found for sale in the UK matched products in the OPSS’ two highest categories of risk, with 98% matching reports described as posing a ‘serious’ or ‘high’ risk to consumers [9].

For each of the products we found for sale online, marketplaces have had ample time to react to the OPSS’ report. For 95% of the products we found available to UK consumers, online marketplaces had had at least 28 days to remove products from sale, and every single listing was found at least seven days after the relevant warning was made by the OPSS. The average time between a warning being raised and our finding a product available for sale was 175 days, or just under six months.

The fact that, for almost a third of products flagged by the OPSS in the last year, we found similar or identical products for sale to UK consumers – often months after the alarm was sounded – shows that online marketplaces are failing to keep consumers safe.

Visible vs invisible risks

Every one of our matches was assessed by analysts as looking highly similar or identical to an OPSS flagged product. For one in four of these (26%) we were able to visibly verify that the safety risk flagged by the OPSS – a small, detachable part, for example – was present. Others posed a risk which was hidden – for instance, faulty internal wiring within electrical products.

Products which pose a visible risk are explored in detail in Chapter 3.

Chapter 3: Clear and present danger

While examining listings on online marketplaces whose images matched a product pictured in a safety report, Which? analysts found 204 listings, each for a product available to UK consumers, in which the risk highlighted by the OPSS was still clearly present in the product being advertised. This was possible either because a product was intrinsically dangerous due to a feature of its design, or because a product visibly possessed a feature flagged as dangerous by the OPSS.

If sold as marketed online, each of these products would be unsafe for sale and therefore illegal. The General Product Safety Regulations 2005 prohibit the sale of products in the UK that are not deemed to be safe.

Products which were intrinsically dangerous

We found 150 products available in the UK which were intrinsically unsafe for their advertised use, accounting for almost three quarters (74%) of products we found with a visible risk. These products included baby sleeping bags which carry a serious risk of suffocation, expanding water beads marketed as toys which pose a serious choking hazard, and electronic items with clover-shaped plugs which could lead to electrocution. Each of these product categories have been the subject of repeated warnings from the OPSS and others [10].

Age warnings and recommendations

Some products identified during this project, including those which are intrinsically dangerous, only pose a risk if they are marketed for a certain purpose. In each case we ensured that, where this was the case, this marketing was present – we removed, for example, baby swaddle bags which did not indicate that they were suitable for sleeping.

For toys which could pose a choking hazard, regulations state that any product which poses a potential danger to children under 36 months must carry an explicit warning which is clearly visible to consumers at the point of purchase, even where a product is not intended for children in this age range. Where such a warning was present, we did not code products as posing a risk. We did not, however, exclude products carrying only a recommendation for use by children of age 3+. According to the European Standard, a ‘recommendation for use’ is not equivalent to a warning, which must display a graphic or include ‘Not suitable for children under 36 months’. Recommending a minimum age is not enough to keep consumers safe.

The graphic above shows, on the left, a baby sleeping bag alerted by the OPSS as posing a serious risk of death by suffocation. On the right are a sample of the 71 products we found online while conducting a reverse image search for this single image, each of which was advertised as suitable for babies. In each case, and for all case studies in this report, these images are cropped from screenshots taken of a product listing page, showing the product was available to be shipped to the UK.

The British Standards Institute sets standards for the design of safe products. The relevant standard for baby sleeping bags requires that they have arm holes, and prohibits hoods.

Baby sleeping bags with head coverings are never safe. As a baby moves in its sleep it might slip down into a bag without armholes, or wriggle up into a hood. In each case fabric may cover a baby’s head causing it to overheat or suffocate, which can lead to death. The risk of overheating is also associated with sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

Experts have long warned that these products are dangerous:

- Since 2020, the OPSS has published safety warnings for 29 separate baby sleeping bags, and in March 2025 it launched a campaign alongside The Lullaby Trust to raise awareness of the danger posed by these products.

- The National Child Mortality Database and Child Accident Prevention Trust have both published warnings about the risks of unsafe sleeping products for babies and guidelines for safe sleeping.

- In 2020, Which? tested 15 baby sleeping bags, and found 12 to be unsafe, in some cases due to a hood.

The OPSS has been working with online marketplaces to remove products, but our findings show these products continue to be available to UK consumers.

2025 Which? investigation

Despite overwhelming evidence that these products are unsafe, Which? found dozens of baby sleeping bags for sale on online marketplaces during this investigation. Concerned about the immediate risk to life, we decided to run a separate investigation into these products in August 2025, drawing on a sample of the sleeping bags found in this research.

While some marketplaces removed the products upon being notified, others were less responsive. Initially, Amazon refused to take down any of the baby sleeping bags that we reported, claiming that ‘the products flagged are not in scope of the safety alerts shared by Which?’. This was despite all of the reported sleeping bags clearly failing to meet safety standards, regardless of specific differences between details in the OPSS report (eg brand name or ASIN, Amazon’s internal ID number) and the listings. After we pointed out that there is simply no safe, legal baby sleeping bag with a hood or without armholes, Amazon removed eight out of the 12 products that we flagged.

Less than two weeks after their first check, our investigative journalists found two dozen identical or similar products still available across online marketplaces, and concerningly, this research has turned up many more.

Products for which the OPSS flagged risk was clearly visible

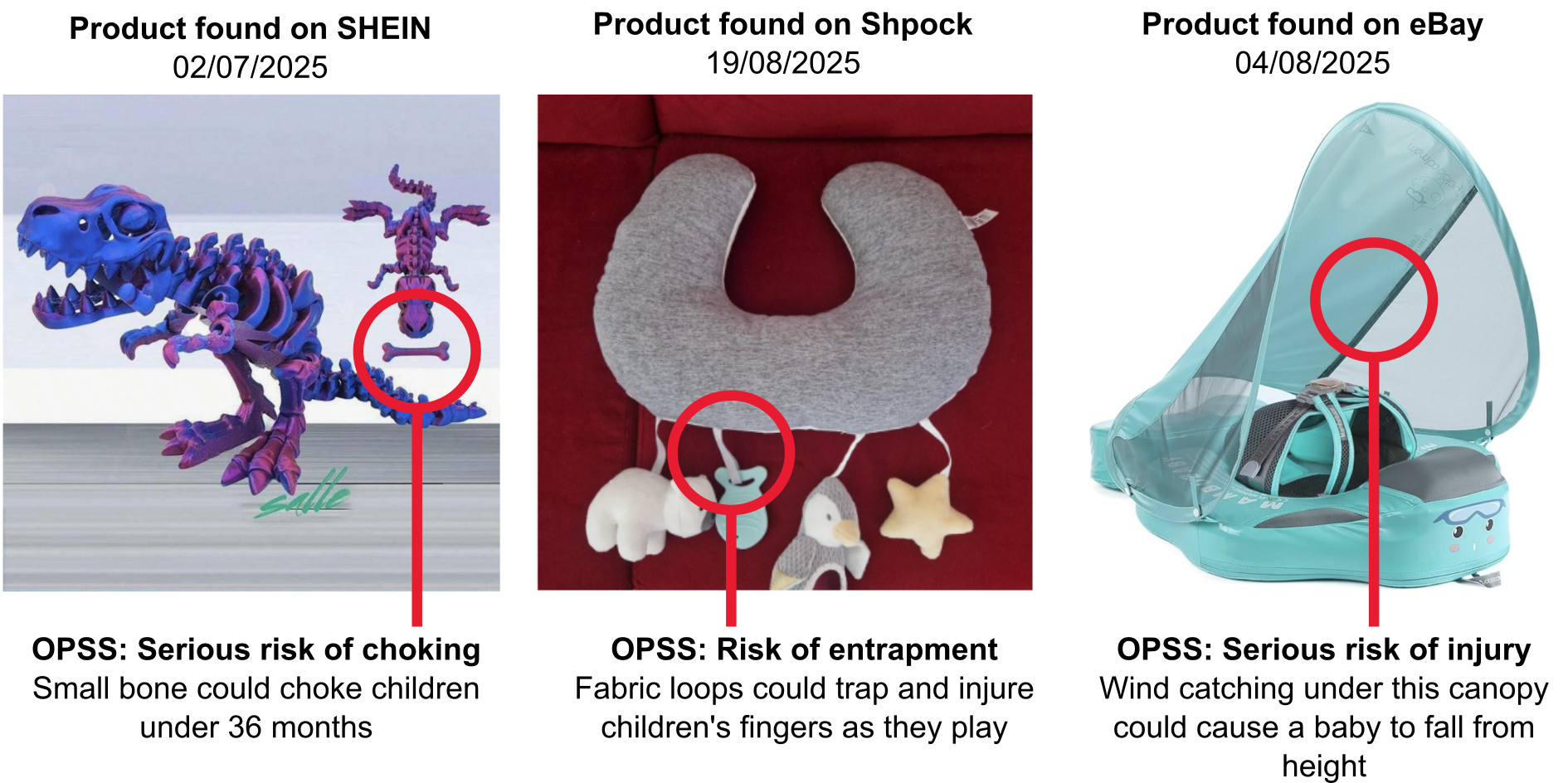

For 54 of the matching products we found on online marketplaces, the risk flagged by the OPSS was clearly visible in the product image.

Figure 2: Examples of products available in the UK where the OPSS flagged risk was clearly visible

These products aren’t intrinsically unsafe: there are safe ways to attach toys to baby pillows, or design a 3D-printed dinosaur. In each of these cases, however, the hazard flagged by the OPSS – usually a physical feature of the product (small parts, straps, loops, etc.) or lack of a feature (eg a protective cover or English markings) was visibly present in the listing. More than four fifths of the products we found with this type of visible danger (82%) pose a risk to children – for example, the wooden toy shown below.

In July, the OPSS issued a report for this Montessori Sound Tree – a wooden musical toy which includes a handful of small balls. When tested, Trading Standards found these balls fit fully inside a small parts cylinder, designed to mimic the size of an infant’s windpipe. This makes the toy unsuitable for young children.

Despite this warning, we found nine of these toys for sale on online marketplaces and marketed to this age range, each clearly showing the presence of small parts. These products, as marketed, would be illegal to sell in the UK.

Every one of the products we found in this category could have been prevented from reaching consumers. In each case, all of the information needed for a marketplace to realise these products were dangerous – the OPSS alert illustrating the danger, the images found in the listing, and, where relevant, the listing text falsely implying it was suitable for a specific use – was freely available to marketplaces, and likely contained on their own systems. That we were able to find any of these visibly dangerous products for sale, let alone 54 of them, represents a damning failure by online marketplaces to live up to the trust placed in them by UK consumers.

Chapter 4: Uncovering hidden risks

All of the products discussed in this report were judged by Which? analysts to be highly similar or identical to a product described and pictured in an OPSS report. As described in Chapter 1, we set a high bar for this similarity, discarding matches that didn’t share characteristic design features, for example, or where the original image wasn’t of sufficient quality.

However, for many of these matching products, and unlike the examples above, the risk flagged by the OPSS was invisible to consumers. Hazards like faulty fuses, the presence of a dangerous chemical, or material weakness are usually not possible to verify from an online listing. While we can’t be completely certain about the danger to consumers in these cases, the visual similarities – between these products and ones where the risk is certain – are marked. As such, Which? is concerned that they’re likely to pose the same risk. Where this is the case, they would be illegal to sell in the UK.

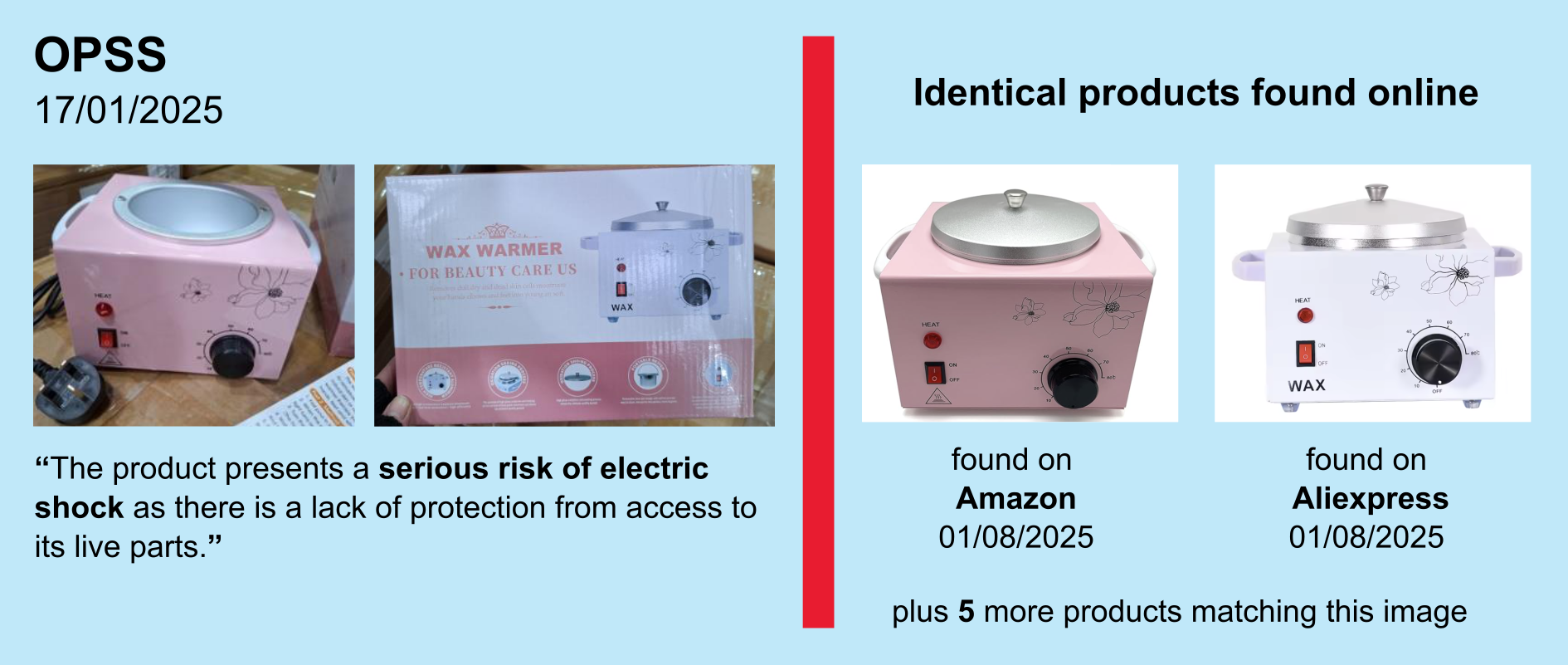

Pictured above is a machine to heat up wax used cosmetically to remove hair, tested and found to pose a serious risk of electric shock by the OPSS. While the products on the right clearly match the OPSS’ images on the left, it’s impossible to determine whether they pose the risk of electric shock from images alone.

The reciprocating saw shown above was flagged by the OPSS due to risk of fire and electric shock. Our investigation found dozens of these saws for sale to UK consumers, across multiple marketplaces. Despite superficial differences in brand labeling and colour, each of these saws shared the same characteristic design features.

When we ordered the KATSU saw pictured above from Amazon and had it lab tested, we found it posed serious safety risks – it did not meet the Supply of Machinery (Safety) Regulations 2008 and is illegal to sell in the UK.

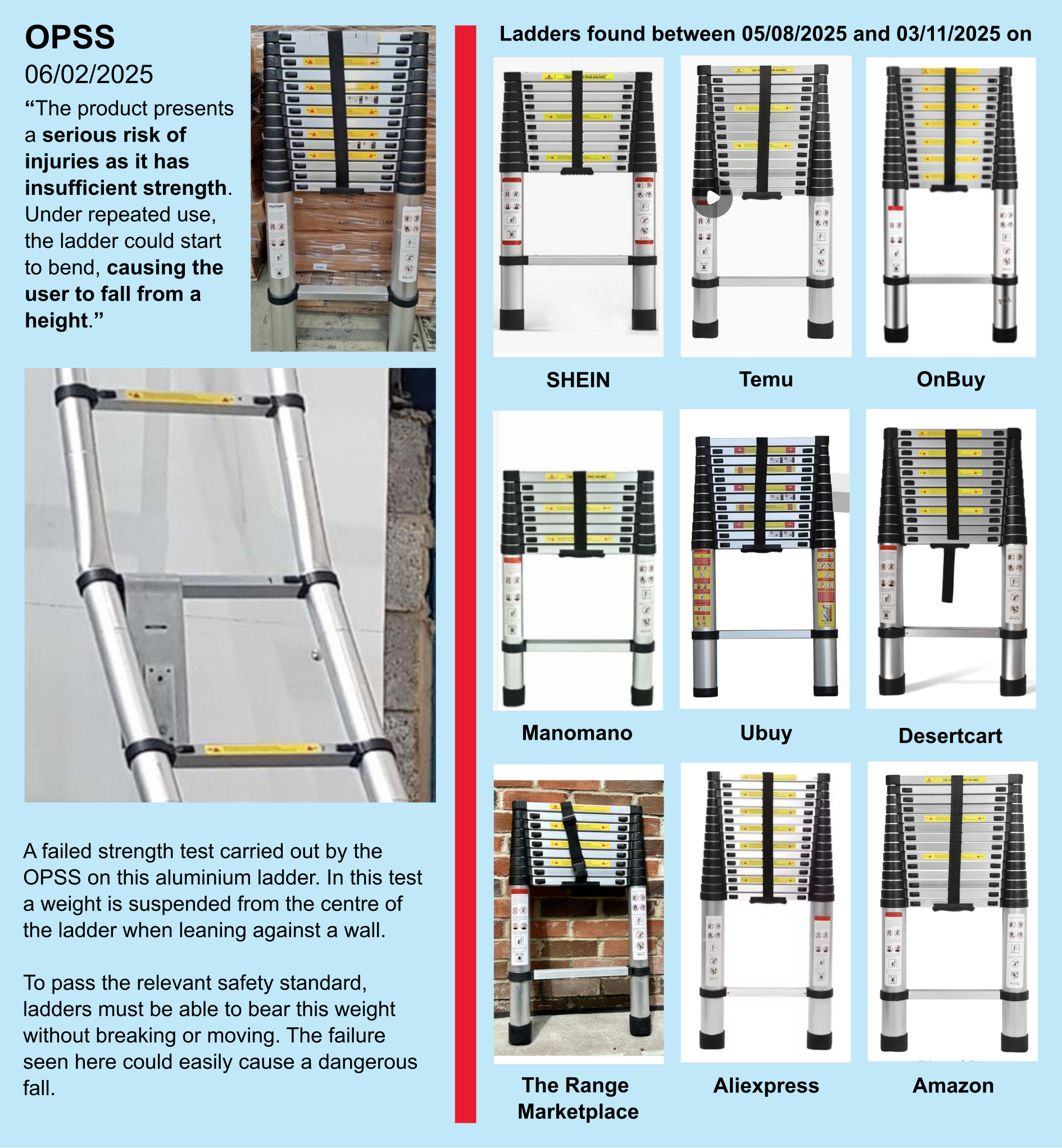

For some of these products, OPSS reports make the risk to life alarmingly clear. Case study 5, below, shows on the left an aluminium ladder tested to destruction by the OPSS, in one of 53 separate safety reports concerning telescopic ladders published by them since 2021.

In the course of this investigation, we found 142 ladders near-identical to the ladder pictured in the OPSS report for sale in the UK, across 21 different platforms.

When the Ladder Association carried out safety tests on 14 ladders purchased from online marketplaces in October 2025, they found that every single one of them failed and posed a significant safety risk to consumers. These failures included 9 separate ladders matching the design pictured above. Alarmingly, 86% of the ladders which failed these tests were fraudulently marked or marketed as conforming with the relevant safety standard, EN 131.

Checking compliance with this standard would be a simple way for marketplaces to ensure any telescopic ladders they sell are safe. By requiring sellers to enter a certification number for a product when it is listed, and then checking the validity of this certificate with the relevant authority, marketplaces could be confident they were keeping deadly ladders from their platforms.

In 2015, a tragic death involving a telescopic ladder prompted the publication of a Prevention of Future Deaths Report – a formal public warning issued when a coroner investigating a death believes that action should be taken to prevent deaths in future. We find it deeply concerning that 10 years later, and despite overwhelming evidence that poorly designed telescopic ladders pose a risk, we are able to find so many of these products available to UK consumers online.

The case studies above illustrate three crucial points which arose repeatedly during this investigation:

The wax warmer is an example of an image from an online listing which is a clear visual match with OPSS imagery – close enough for automated image searching to find, and certainly for human review to confirm. It is not unrealistic to expect marketplaces to be able to find these products.

The electric saw shows that some dangerous products cannot be identified by relying on indicators like model names, brand names or product IDs internal to marketplaces. A serious attempt to identify dangerous products must expect some variation in these identifiers.

The telescopic ladder shows that dangerous products can spread across multiple marketplaces, and presents a clear case where a small amount of due diligence to require and check compliance with a standard could prevent dangerous products from reaching consumers.

Products matching an OPSS report: two possibilities

For each matching product with a hidden risk found on online platforms, there are two possible explanations as to why they look so similar to a product flagged by the OPSS:

- Despite looking the same, the products we found on marketplaces are either entirely different products to those appearing in reports, or have been altered by manufacturers in a way that removes the risk flagged by the OPSS, making them safe without changing their outwards appearance.

- The products we found on marketplaces look the same as those flagged by the OPSS because they are the same, and pose the same risks to consumers.

Testing previously carried out by Which? and others suggests that seemingly identical products are indeed likely to pose the same risks. When Which? tested seven identical versions of the same dangerous heater from different online marketplaces in 2023, every one of them was found to be dangerous. More recently, the British Toy Hobby Association undertook a 2025 study to test products similar to 64 toys which failed tests in 2024. They found that, for 72% of these, a seemingly identical toy was still available for sale on online marketplaces in 2025. When they tested these highly similar toys, 100% of them failed.

In order to establish whether these observations held for the products uncovered in this investigation, we commissioned our own testing, asking independent labs to test a sample of the products we had found for sale in the UK which were highly similar or identical to products flagged as dangerous by the OPSS.

Lab testing results

We selected a sample of 15 products from the two most prevalent categories flagged by the OPSS – 13 electrical products, and 2 toys [11].

- Electrical products included hair styling tools, an extension cable, two electrical power tools, plug-in heaters, a bathroom lighting instalment, and a bedside lamp.

- The toys tested were a fidget spinner and busy board marketed as suitable for babies.

Each product was identified as matching an OPSS report and either had a hidden risk, or a visible risk we wanted to assess was still there. Each was also available to UK consumers from an online marketplace at the time it was found. This selection was chosen to include a range of types of goods, including products for which it was possible that a manufacturer had replaced a failing part, such as a non-compliant plug or a toy part posing a choking risk.

All of the 15 products we tested failed to pass UK product safety regulations. Of these 15:

- 14 failed because they are unsafe for use. They are constructed in such a way that poses an active risk to consumers’ safety.

- 1 failed only due to illegal labelling. The fidget spinner we tested was found to be safe, but was missing conformity or traceability markings and so does not meet UK product safety regulations.

Our tests found that every single product had at least one issue with product markings or packaging – a missing model number, lack of recommended electrical ratings, or in a couple cases, lack of crucial safety warnings like not to use the product near water.

Electrical Products

Independent lab testing of electrical products found that all 13 failed to meet at least one relevant safety standard, and posed an immediate danger to consumers [12].

As expected, most of these failures had already been identified by the OPSS – 10 out of 13 products posed the exact same risk as the one identified by the original safety report. This was not always possible to assess: one product, for example, was flagged by the OPSS due to a faulty adaptor, but as the sample didn’t arrive with an adaptor the original risk couldn’t be assessed. Nevertheless, whether these failures matched the OPSS flagged risk or not, each electrical product failed critical safety tests.

Failures were varied in nature, with samples we tested raising an average of 13 separate safety issues each. Most products posed serious fundamental safety issues:

- Nearly all of the products we tested (11 out of 13) had hidden internal faults, with problems ranging from dodgy wiring and soldering to missing thermal protection

- More than half (8 out of 13) were provided with noncompliant or counterfeit plugs

- 5 out of 13 had issues arising from the way they were put together (eg allowing access to live parts, presence of sharp edges, etc)

Our testing showed that each of these products is seriously dangerous, and puts consumers at risk of injury, electrical shock, or fire.

Toys

Both of the toys we tested were non-compliant with UK toy safety regulations. The Montessori busy board presented the same issue as originally flagged by the OPSS – small detachable parts posing a choking risk – along with additional risks – multiple loops that pose an entrapment risk. The baby fidget spinner had incorrect and misleading labelling, suggesting the toy was intended for children under 36 months, but also warning of a choking risk.

This testing was only carried out on a small sample of the products we found which look identical to those flagged as dangerous by the OPSS, and our results here cannot be used to pass definitive judgement on all products for sale online. Nevertheless, the fact that we found major safety issues in nearly every product tested raises real concerns about other seemingly identical products for sale online.

Chapter 5: How could online marketplaces respond?

Many online marketplaces already have systems in place to address the problem of unsafe products [13]. Annual transparency reports highlight large numbers of listings blocked: eBay report using an AI-driven product safety algorithm to block 41 million violations in 2024, and Etsy claim to have removed 50,000 items through a system which ‘continuously and proactively scan[s] [the] platform for recalled items’. Platforms have repeatedly made public commitments to ambitious targets in this space – eBay, Etsy, and Amazon have all made international product safety pledges which outline, as Amazon puts it, ‘aspirations for modernization in the field’.

These same reports show that online marketplaces have the resources to invest in cutting edge technologies for identifying illegal and non-compliant products. Some report using image detection as part of their product safety filtering process. Others cite their use of advanced computer vision and image recognition, similar to the reverse image searching technology used by Which? in this research, to identify and remove products that infringe upon intellectual property rights. Our findings suggest that, despite these claims, marketplaces are failing to live up to their product safety aspirations.

The results of this investigation have highlighted that the current legal regime results in businesses having too much flexibility to determine how similar a product must be to an OPSS alert before acting; for example by requiring that a listing number is directly cited in an OPSS report. This lack of clarity leaves consumers exposed to dangerous products. We found, purchased, and tested products during this investigation that, while looking highly similar or identical to a flagged item, would not have been found by searching for the specific product identifier, or even brand, listed in an OPSS alert. Due diligence must apply to products likely to cause the same harm; products which Which? were able to find using a mix of publicly available and self-built tools, and a team of two data scientists.

One possible response to OPSS warnings could be a risk-based, precautionary approach informed by the following framework:

- Where the OPSS has shown that a category of products with a specific design poses an intrinsic risk, eg hooded baby sleeping bags, all products falling under this category should be identified and checked to ensure the flagged risk isn’t present.

- Where a product image is sufficiently similar to a current or historical image published by the OPSS, that product should be compared with the OPSS alert.

- In cases where the risk flagged by the OPSS is clearly visible, the product should be prevented from reaching UK consumers.

- In cases where the risk is hidden – eg an electrical fault – marketplaces should ensure that the seller can prove the product does not pose that specific risk, eg through requesting and verifying compliance with a relevant safety standard.

- Marketplaces should be required to make these checks when a listing is first made by a seller, removing products likely to be dangerous before they become available to consumers in the first place.

We believe these checks, which react to OPSS reports, are proportionate. Based on the evidence presented above, they are also likely to be effective in preventing a large number of unsafe products from reaching consumers in the UK. Taken alone, however, a reactive approach which relies on reporting by the OPSS or Trading Standards will be insufficient to keep people safe. If true progress is to be made in this area, we are likely to need new legal requirements on platforms to be proactive in undertaking this work. We lay out some recommendations for these below.

Recommendations

The findings from this report provide yet more evidence of the shocking extent to which online marketplaces are currently able to act outside of the established product safety regime and how safety law is too weak to prevent dangerous products from reaching households in the UK.

Online marketplaces are failing to take even the basic step of acting on official product recalls to protect consumers from unsafe and illegal products. Yet consumers are buying from these platforms in ever growing numbers, unaware of the lack of protection and therefore risk they are exposed to. This legal loophole is not trivial: in the UK people have lost their lives, homes and experienced serious physical harm as a result of dangerous products sold through these platforms.

Our investigation shows how feasible it is for online marketplaces to conduct vital checks – but they aren’t doing this. It is possible to identify unsafe products subject to OPSS safety alerts relatively easily. But without the necessary legal incentives, it is unlikely that marketplaces will take the proactive action needed to prevent unsafe products from being sold on their platforms, if they aren’t even acting on these official alerts.

Online marketplaces must be held accountable for the safety of products sold on their platforms, including those from third-party sellers. To properly protect consumers, the government must introduce new secondary laws that put consumer safety first. These must ensure that online marketplaces take proactive steps to prevent unsafe products being listed, carry out effective monitoring to identify unsafe products and take effective action to swiftly remove unsafe products and provide appropriate notifications and information to consumers when they are identified.

The government must urgently come forward with secondary legislation under the PRaM Act that places specific duties on online marketplaces to ensure the safety of the products that they sell. These should include:

- A requirement to take a proactive approach to ensuring listings are safe. This includes checking and verifying their sellers and taking steps to ensure that they are compliant with UK safety requirements and relevant standards, including provisions of valid certification and making this information transparent to consumers.

- A requirement for regular monitoring to identify and take down any potentially unsafe products. Once removed, these products must not be allowed to reappear under a different name or seller without proper checks. The current ‘whack-a-mole’ approach puts lives at risk.

- As part of this, a requirement to monitor and act on safety alerts and product recall databases from official bodies. When a product is flagged as unsafe or illegal, online marketplaces should be required to remove it from sale immediately.

- A legal requirement to contact affected customers directly. Online marketplaces should provide clear, timely information on the risks and what steps to take next.

- When a product looks identical or highly similar to one identified as unsafe by the OPSS, online marketplaces should adopt a precautionary approach and remove the items immediately. It should not be necessary to wait for conclusive testing and proof of the harm before taking action to prevent it.

- Online marketplaces should also be subject to requirements that ensure that consumers are provided with appropriate information, instructions and warnings about products. This also includes making it clear to consumers who they are buying from so that they know when they are buying from a third-party seller and a trader, rather than an individual consumer.

The Regulations should also place obligations on online marketplaces to cooperate with regulators, including responding to requests for information and taking actions required to prevent the availability of unsafe products and to help identify them. International platforms that sell to UK consumers must not be allowed to dodge their responsibilities. In order to respond effectively and rapidly to requests from the regulator, they must appoint a UK-based legal representative. This representative should be accountable to safety authorities and able to support customers when things go wrong.

Regulations should clarify liability when consumers buy an unsafe product. The law must leave no room for doubt: if a product sold on a marketplace causes harm, the platform itself can be held liable to provide redress. This is essential to ensure consumers can seek justice. It also sends a powerful message to platforms that safety must come first.

Regulators must be equipped with the power to enforce these obligations, including issuing meaningful financial penalties. It is imperative that the new safety framework is supported by a powerful deterrent for non-compliance.

A coordinated, intelligence-led system is essential to tackle unsafe products effectively so that regulators can act swiftly and proactively. This requires a framework that fosters seamless coordination and intelligence sharing, not only within the UK but also with international partners. For example, between the OPSS’s Product Safety Database and the EU’s Safety Gate to facilitate rapid identification of products that present a risk that are available in both markets.

The above actions are needed to ensure that the product safety regime is fit for purpose to address the gaps that exist in relation to online marketplaces and related responsibilities. Online marketplaces, however, should not wait for legislative change to improve the safety of the products listed on their sites. Our research has shown that it is possible for them to improve the effectiveness of the checks that they take immediately.

Annex A: Technical Annex

Stage 1: Collecting Data

Using a web scraper built in Python using the selenium package, Which? collected every available report from the Office for Product Safety and Standards Product Recalls and Alerts list at https://www.gov.uk/product-safety-alerts-reports-recalls, gathering information including:

- Alert date

- Product category

- Risk level

Alerts gathered went back to January 2021. Many included a link to a pdf which described the flagged product in further detail. Where safety alerts had an associated pdf, the Python module camelot was used to extract information from it, including:

- Product type

- Production description

- Product identifiers (eg brand, model number)

- Risk type

- Risk description

- Online marketplace of listing

PDFs usually contained images of the product taken by the OPSS or Trading Standards officer who flagged it. These images were extracted using the excellent pdf2txt feature of the module pdfminer.six, and saved to a database.

This data was filtered in two ways:

- By date: taking alerts published between 1 August 2024 and 11 August 2025

- By product: removing all non-consumer products (eg commercial machinery or groundmoving equipment)

Stage 2: Building an image annotation tool

Which? built a custom browser-based tool designed to retrieve information from a selected OPSS alert, displaying detailed information about an alert and all images included in it. The tool then prompts analysts to perform a Google Reverse Image search on any images included in an OPSS report image, displaying results in a grid and helping users to review and label them. Any resulting matches, along with any relevant labelling, are then saved directly into a database.

Stage 3: Identifying matches

Using the browser-based tool described in Stage 2, Which? checked 1,036 images from 702 alerts published by the OPSS between 1 August 2024 and 11 August 2025. For each image, analysts coded the top 25 matching results from a Google Reverse Image search, each of which was coded as following:

- If a product was a visual match or visibly posed the same risk as the one flagged by the OPSS, it was coded as one of category 1, 2, or 3 (described below)

- If the product was on sale to UK consumers this was recorded, and a screenshot was taken as proof

Matches were categorized as follows:

Category 1: Products that are intrinsically dangerous by virtue of their design

Category 2: Products which visibly pose the same risk as that flagged by the OPSS

Category 3: Products that look identical or similar to unsafe products

Native search

Since the results of the process above were heavily impacted by Google’s indexing of webpages, Which? also manually searched for products on a range of online marketplaces. 17 online marketplaces were chosen based on those found to be commonly used by consumers in a previous Which? survey of consumers’ online shopping habits, those included in an OPSS testing program, and those for which we had already found matches using the automatic matching tool.

4 products were chosen that were representative of concerning types of unsafe products:

- A baby sleeping bag with a hood

- An aluminum telescopic ladder

- Expanding water beads sold as a toy

- A handheld reciprocating saw

For each product, and on each online marketplace, we searched for relevant keywords or - where platforms had built-in image search capabilities - the image from the OPSS alert to identify matching products.

Annex B: Full responses from marketplaces

We contacted 28 marketplaces to let them know we had found at least one product that appeared similar or identical to a product in an OPSS alert for sale on their platform. Here we include responses from those that are named in this report, or whose products we ordered and tested.

Desertcart, Ebuy7, Etsy, Manomano, OnBuy, Shpock, and Ubuy didn’t respond.

The Range declined to comment.

Amazon

“We require all products offered in our store to comply with applicable laws, regulations, and Amazon policies, and we proactively monitor our store for safety alerts and product recalls and remove relevant products and email customers who purchased them.

Safety alerts are specific to an individual products' unique characteristics, including brand name, model number or design features, and our initial findings show that the vast majority of products highlighted by Which?’s research do not fall under the scope of these alerts.

Out of an abundance of caution, we temporarily delisted the products tested by Which? and will remove any non-compliant items identified by our investigation and further refine our controls.”

AliExpress

“AliExpress takes product safety very seriously and we have strict rules and policies in place to ensure a safe online shopping environment. Third-party sellers who list items for sale on our marketplace must comply with the applicable law as well as our platform rules and policies. We have been and will continue to work closely with the OPSS and other regulators to prevent non-compliant product sales on our marketplaces.”

B&Q

“We take the safety of products sold by third-party sellers on B&Q Marketplace very seriously. This includes conducting proactive checks, monitoring all UK and EU safety notices, and using technology to prevent recalled products from being listed for sale.”

eBay

“Consumer safety is a top priority for eBay. We have reviewed the listings identified by Which? and taken action where required, including removing items and notifying buyers where appropriate. We’re reviewing the wider marketplace to remove any identical listings.

We work diligently to prevent and remove unsafe product listings through seller compliance audits, block filter algorithms, AI-supported monitoring by in-house specialists, and close partnerships with regulators. Several of the unsafe listings highlighted by Which? had been removed or ended before the investigation was shared with eBay, showing how existing filters and monitoring systems work to reduce unsafe products on the site.”

Fruugo

Fruugo maintained that it is not a retailer in its own right and has no opportunity to inspect products on the platform, but proactively sweeps the platform for high risk listings.

A Fruugo spokesperson said:

“We take these issues extremely seriously and we understand the importance of ensuring retailers using our platform meet their legal and product safety obligations.

That's why we have a full product recall and withdrawal process including an effective notice and take down process that ensures non-compliant products such as these are quickly removed from sale.

We can confirm that the items you brought to our attention have all been withdrawn from the Fruugo platform and a product recall is in progress for any units of the affected items sold.”

Shein

“On SHEIN Marketplace, all vendors are required to comply with SHEIN's code of conduct and abide by the relevant laws and regulations of the countries where we operate. When non-compliant items are found, SHEIN takes immediate action to remove them, and we are continuously working on improving our processes to prevent these items from reappearing on our site."

Temu

Temu said they take compliance with their regulatory obligations very seriously, including by monitoring product recall and safety alerts issued by the OPSS and regulatory authorities. Temu said "We reviewed the 26 product listings as soon as we received your inquiry and found that none of them fall under the safety recalls. Twelve of the listings had already been discontinued before your inquiry. We have removed the remaining 14 listings as a precaution and are expanding our review to similar products to ensure they meet the required safety standards.

TikTok

“The safety and trust of our customers is a top priority and we strictly prohibit the sale of any products recalled by government or regulatory authorities.

Many of the items in question had already been removed, and we have taken further action to promptly remove the small number of remaining products that do not comply with our policies.”

Footnotes

[1] Online Poll with 2,096 UK adults. The data is weighted to represent the adult population of the UK by age, gender, region, social grade, working status and housing tenure. The survey took place from 5th to 6th November 2025. The 24 million figure is based on 44% of UK adults buying from an online marketplace at least once a month. ↑

[2] Which? (2025) Return of 'killer car seats' - fabric seats spotted at checking event.

Which? (2025) Dangerous baby sleeping bags found for sale on online marketplaces.

Which? (2025) Which? investigation finds at least two thirds of cosmetics it bought from online marketplaces may be counterfeit.

Which? (2025) Kids' sunglasses bought on online marketplaces unsafe and Illegal in the UK.

Which? (2025) How we were able to easily list illegal products for sale on online marketplaces.

Which? (2024) Illegal and potentially dangerous ‘energy-saving’ plugs still widely available.

Which? (2024) Over 90% of toys we bought from online marketplaces 'illegal' to sell in the UK.

Which? (2024) Why you should avoid unbranded electronics on online marketplaces.

Which? (2024) Electric heaters sold on TikTok and Temu could explode, cause electric shocks or start a fire.

Which? (2023) Illegal weapons and age-restricted items sold without checks on Temu.

Which? (2023) Killer carbon monoxide alarms still on sale through online marketplaces. ↑

[3] London Fire Brigade (2025) London faces record number of e-bike fires in 2025 as calls for more urgent awareness grow. London Fire Brigade. #ChargeSafe: E-bike and e-scooters are London’s fastest-growing fire trend. ↑

[4] Undercover seller investigations: Which? (2025) How we were able to easily list illegal products for sale on online marketplaces. Which? (2019) Dangerous toys and killer car seats listed for sale at online marketplaces like Amazon and eBay. ↑

[5] Online Poll with 2,096 UK adults. The data is weighted to represent the adult population of the UK by age, gender, region, social grade, working status and housing tenure. The survey took place from 5th to 6th November 2025. Estimate based on one in six of those purchasing from an online marketplace in the last two years reporting an issue with their product (18%). Base sizes: Purchased from online marketplace in the last two years (1,857). ↑

[6] Environmental Health Officers based within local authorities are responsible in Northern Ireland. ↑

[7] In most browsers, you can see this by right clicking on any webpage and selecting ‘View page source’. ↑

[8] See eg reports by: Shein (2024) Sustainability and Social Impact Report.

Amazon (2024) Amazon’s approach to product safety in Europe.

eBay (2024) Global Transparency Report.

AliExpress (2025) DSA Biannual Transparency Report.

Temu (2025) Temu Transparency Report.

Etsy (2024) 2024 Transparency Report. ↑

[9] As defined by the OPSS Product Risk Assessment Methodology, these risk levels typically reflect an evaluation of both the severity and probability of the possible harm. A high or serious risk would generally be considered “intolerable” by the public. More detail at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/66fd385ae84ae1fd8592ec93/prism-guidance-v02.pdf. ↑

[10] OPSS (2024) Product Safety Alert: Water Beads (PSA7). Electrical Safety First (2024) Households urged to check if their Christmas gift is a fire risk by checking its plug. ↑

[11] While significant evidence has been published on the availability of dangerous toys on online marketplaces by the British Toy and Hobby Association, various factors meant that we were able to test fewer toys here than we had intended to. Future work into this question would ideally address this imbalance. ↑

[12] Each tested electrical product failed at least one of the electrical Equipment (Safety) Regulations 2016, Plugs and Sockets etc. (Safety) Regulations 1994, or Supply of Machinery (Safety) Regulations 2008. ↑

[13] Amazon, Preventing Unsafe Products in Our Store.

Amazon (2024) Amazon’s approach to product safety in Europe.

Shein (2024) Sustainability and Social Impact Report.

eBay (2024) 2024 Global Transparency Report.

AliExpress (2025) DSA Biannual Transparency Report.

Temu (2025) Temu Transparency Report.

Etsy (2024) 2024 Transparency Report. ↑